Confessions of an Antediluvian Geek - A personal history of computing

Part Four - Blip... Blip... Blip...

I finally graduated, and my first real job was working for a small electronics company

as a programmer in their business computer department, which at that time was called

"Management Information Systems", or just MIS. Nowadays, they call the same thing

the Information Technology, or IT department. The work there was run-of-the-mill programming

on an IBM System/360 Model 30, one of the smaller machines. After a couple of years, I

moved on to a much more interesting job at a company called Grumman Data Systems.

This was a subsidiary of the Grumman Aircraft Company, which was, at the time, one of

the largest military aircraft manufacturers. As a big aircraft engineering and manufacturing

company, Grumman had a lot of computers and a lot of programmers, and, as was the fashion

in those days, decided to "spin off" their computer operations into a subsidiary company

and make it a profit center. I went to work for a small sub-sub-division, which

was in the process of attempting to design and fabricate, and ultimately sell a very

large storage device, called MassTape. This was a set of very big boxes, not unlike

the mainframe computers of the day, which used state-of-the art tape cartridges that used

a magnetic tape technology originally developed for the Apollo program. I was

supposed to help with the software that was needed to control the device and also

to catalog the huge amounts of data it was supposed to hold. The biggest configuration they

planned to have was to be capable of holding a terabit. For comparison, that

little 200 Gigabyte disk drive in your laptop holds more than that.

I finally graduated, and my first real job was working for a small electronics company

as a programmer in their business computer department, which at that time was called

"Management Information Systems", or just MIS. Nowadays, they call the same thing

the Information Technology, or IT department. The work there was run-of-the-mill programming

on an IBM System/360 Model 30, one of the smaller machines. After a couple of years, I

moved on to a much more interesting job at a company called Grumman Data Systems.

This was a subsidiary of the Grumman Aircraft Company, which was, at the time, one of

the largest military aircraft manufacturers. As a big aircraft engineering and manufacturing

company, Grumman had a lot of computers and a lot of programmers, and, as was the fashion

in those days, decided to "spin off" their computer operations into a subsidiary company

and make it a profit center. I went to work for a small sub-sub-division, which

was in the process of attempting to design and fabricate, and ultimately sell a very

large storage device, called MassTape. This was a set of very big boxes, not unlike

the mainframe computers of the day, which used state-of-the art tape cartridges that used

a magnetic tape technology originally developed for the Apollo program. I was

supposed to help with the software that was needed to control the device and also

to catalog the huge amounts of data it was supposed to hold. The biggest configuration they

planned to have was to be capable of holding a terabit. For comparison, that

little 200 Gigabyte disk drive in your laptop holds more than that.

Well, the engineers had been working for quite a while when I joined, and there was

a prototype, but it didn't really work very well, and so while the engineers were

re-thinking and re-designing, us programmers had some time to "play". One of the things we

got to play with, and do real work on as well, I should add, was the first Personal Computer.

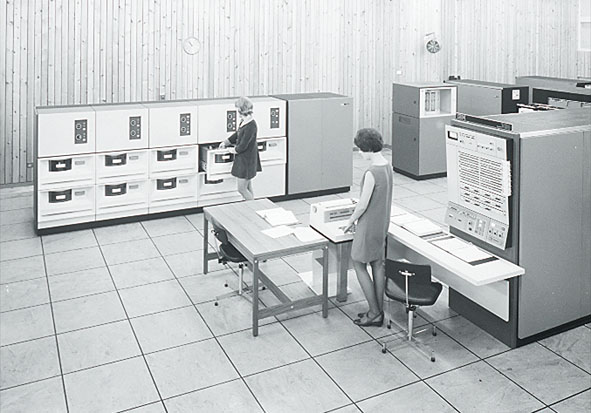

No, not what you're thinking. See the picture. That's a personal computer. (I wish

to make it clear that we didn't have ladies like that working in our computer room, Alas.)

The machine is the picture is an IBM System/360 Model 67, and it was a major breakthrough

in computing back then, and its' impact is still being felt today. It supported something

called timesharing. It also was one of the first machines, and I think the first commercially

available machine to support something called Virtual Machines, which is beyond the scope of

this story.

Well, the engineers had been working for quite a while when I joined, and there was

a prototype, but it didn't really work very well, and so while the engineers were

re-thinking and re-designing, us programmers had some time to "play". One of the things we

got to play with, and do real work on as well, I should add, was the first Personal Computer.

No, not what you're thinking. See the picture. That's a personal computer. (I wish

to make it clear that we didn't have ladies like that working in our computer room, Alas.)

The machine is the picture is an IBM System/360 Model 67, and it was a major breakthrough

in computing back then, and its' impact is still being felt today. It supported something

called timesharing. It also was one of the first machines, and I think the first commercially

available machine to support something called Virtual Machines, which is beyond the scope of

this story.

Before timesharing, as I mentioned in a previous story, computers ran

in "batch mode". Programs were submitted to the computer operators, gathered into batches,

run until the last one in the batch had finished, the output taken off a high speed printer,

and the results distributed. This process took hours, or even days. Timesharing gave each

user a little tiny portion of the computer time, say a few milliseconds, and then went on to

the next user, and eventually came back again. This gave you the

illusion that you had the computer all to yourself.

In addition, the timesharing system was interactive,

which meant that you typed something to the computer, got an answer, and typed something again,

very much like it is today on your personal computer. Finally, you didn't have to be in the

same room as the computer. You worked at something called a "terminal", which in those days

looked like a big electric typewriter.

Before timesharing, as I mentioned in a previous story, computers ran

in "batch mode". Programs were submitted to the computer operators, gathered into batches,

run until the last one in the batch had finished, the output taken off a high speed printer,

and the results distributed. This process took hours, or even days. Timesharing gave each

user a little tiny portion of the computer time, say a few milliseconds, and then went on to

the next user, and eventually came back again. This gave you the

illusion that you had the computer all to yourself.

In addition, the timesharing system was interactive,

which meant that you typed something to the computer, got an answer, and typed something again,

very much like it is today on your personal computer. Finally, you didn't have to be in the

same room as the computer. You worked at something called a "terminal", which in those days

looked like a big electric typewriter.

The timesharing system at Grumman Data Systems was called CP-67/CMS, and was originally written by a small group at the IBM Cambridge Scientific Center as an unofficial project. In fact, IBM never really wanted it, and made it available for free. (Well, it wasn't actually free, you had to pay for the magnetic tape it came on. Ten dollars, I think.) I won't go into the history of CP/CMS, but it was revolutionary, eventually replacing IBM's official timesharing system, called TSS, and becoming an extremely popular operating system, and an official product, called VM/370, now called z/VM.

Working on CP/CMS was the most fun I ever had with a computer. It was liberating, you could write programs as fast as you could type. You could invent new commands for the system, you could do things that you would never have even considered with the old batch systems. It was much like Unix or Linux today, but much, much earlier, and I think had quite a number of advantages. Most people who used it remember it fondly even today. There are many fascinating articles and documents on the Web about CP/CMS and its successor VM/370. Do a Google search, or take a look here.

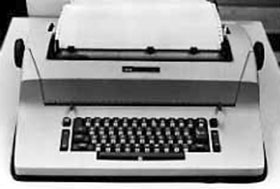

There was one very cute feature of CP/CMS. Today, when you run a program that is

going to take some time, the operating system usually displays a little hour-glass

or even a progress bar to tell you that you have to wait. This doesn't work on

a typewriter terminal. Somebody, I wish I knew his name, came up with a brilliant

idea. The IBM Selectric Typewriter, which was used as the mechanism for the

terminals, had a device called a typeball, which had the upper-case letters on

one half, and the lower-case letters on the other half. If the computer

wanted to switch from one case to another, it sent a signal to the terminal,

and the typeball would rotate 180 degrees. CP/CMS had a feature that

whenever a user's program used 1 second of computer time, it would send signals

to the terminal, saying in effect, "upper-case, lower-case". This would cause

the typeball to rotate 180 degrees, and then immediately rotate back, without

touching the paper. To the user at the terminal, the typeball would twitch, and

make a sound -- Blip. If you had a program running for a while, you could

walk away from the terminal, and just come back occasionally, and if was still

running, you would hear Blip.... Blip.... Blip.... .

There was one very cute feature of CP/CMS. Today, when you run a program that is

going to take some time, the operating system usually displays a little hour-glass

or even a progress bar to tell you that you have to wait. This doesn't work on

a typewriter terminal. Somebody, I wish I knew his name, came up with a brilliant

idea. The IBM Selectric Typewriter, which was used as the mechanism for the

terminals, had a device called a typeball, which had the upper-case letters on

one half, and the lower-case letters on the other half. If the computer

wanted to switch from one case to another, it sent a signal to the terminal,

and the typeball would rotate 180 degrees. CP/CMS had a feature that

whenever a user's program used 1 second of computer time, it would send signals

to the terminal, saying in effect, "upper-case, lower-case". This would cause

the typeball to rotate 180 degrees, and then immediately rotate back, without

touching the paper. To the user at the terminal, the typeball would twitch, and

make a sound -- Blip. If you had a program running for a while, you could

walk away from the terminal, and just come back occasionally, and if was still

running, you would hear Blip.... Blip.... Blip.... .

Copyright © 2007 by Jeff Kravitz